Home > What’s Happening? > Aging with T1D: In Living Color

Aging with T1D: In Living Color

Above is Haidee Merrit and her faithful dog Larkin.

Interviewed for T1D100.com by Barbara Giammona on January 6, 2026.

Haidee Merrit is a New Hampshire-based artist best known in theT1D community as a cartoonist whose three books of diabetes-themed cartoons and illustrations share a humorous, and often edgy, take on life as a type one. She is also a colorful artist whose works are vibrant and lively, often featuring vividly detailed insects or splashy abstract landscapes. She met with us at T1Dto100 to talk about what led her to her specific art forms and her philosophy about living with T1D.

Barbara: Your cartoons and humor have an edge. They speak about common experiences many of us have had.

Haidee: Yes—don’t we all understand these intimacies and insights as long-term type ones?

Although it’s difficult to believe, my first book was published almost 20 years ago. Many of the cartoons in the first volume touch on subjects—whether personal experiences, complications, or technologies—that are increasingly outdated. Although not great for book sales from more contemporary generations, it’s certainly a reflection of positive advancements in the disease—hard to complain about that!

For example, two of the things I reference in One Lump or Two are the annoyance of dull needles and the way a finger stick can create a geyser effect, which is when, from a finger squeezed just the right way, you’re showered with a drizzle of minuscule blood droplets. It was always startling, but also fascinating and, well, gross. Today many of us have CGM technology to keep us aware of glucose levels around the clock and, quite literally, we never even SEE blood! I’m not saying I miss it by any means, but it’s an unmistakable change—older diabetics reading this might commiserate while younger ones can’t relate.

There are some cartoons that touch on the fear that used to be a momentous burden of living with type one: for me, carrying so much of it was a life-shaping, reality-warping way of life. I’m sure all the sociological factors—family of origin, cultural environment, social group—have a lot of influence on each of us, but speaking for myself it was the absolute worst part of growing up. As humans, and especially as diabetics, we adapt—I’d keep rolls of Lifesavers in my socks as I rowed crew down the Charles River, for example—but my mind was always in survival mode, trying to notice minute changes that would indicate low blood sugar. I would worry every minute of every day that a grand mal seizure would end my Latin class if I couldn’t make it to the lunch bell. How do you focus on conjugations? To think of all the mind space I could’ve used on my education or on enjoying the freedom of childhood really is almost cripplingly sad to me sometimes.

Some people reading this interview will identify with this part of diabetes “history,” but thankfully there are fewer and fewer of us.

Barbara: What do you do to care for your diabetes today?

Haidee: I’ve always referred to the diabetes lifestyle as having a fulltime job without a salary (or benefits for that matter). Things have simplified for me in the last 15 years, mostly as a result of technology. Getting a CGM was definitely a life changer for me, something I never want to live a day without—I always say I’d crawl over glass for my Dexcom! I started out as a huge doubter of the early devices but now, I’ll never go back. And I’m also an Omnipod wearer, primarily because I’m both clumsy and active so the tubeless option is my cup of tea.

Oh, and one day, I’d love to have the ability to deliver glucagon! Even if it’s a separate delivery system, not the holy grail of the closed-loop. I can’t tell you the freedom I would feel if I didn’t need to carry sugar everywhere I went (my current choice is 3 fun-size packs of Skittles, 14g of carbs per pack). If you could deliver a little bump of glucagon with a quick press of a button—like morphine delivered after surgery – that would be ideal! And it would prevent the need to eat before exercise! I’m getting excited just thinking about it!

I’ve always felt keeping my brain going and physical activity are my really big ways of controlling my diabetes. And the two are obviously inseparable. Mobility is primary so I’m very conscious of taking care of my feet and legs. Another trick—I keep a barbell over in the corner of my kitchen. When I need to bring my sugar down, I lift a single weight for a few minutes and I’m usually good to go.

Barbara: Being an artist is a “desk job” – you sit a lot. How does that work for you?

Haidee: Good question and, as we all know, no two days are the same in the life of a diabetic. I’m consistently inconsistent! My body seems to use insulin best when I‘m in motion—keeping my metabolism going with activity—so I feel that requires me to have a flexible lifestyle. Not ideal, I’ll admit. Ideally, if I can work at the studio for a few hours, then walk the dog, next eat some lunch, then do some cleaning or lawnmowing, then go back and spend more time at the studio, it works GREAT. Sitting in a cubicle or being a long-distance driver would both be challenging lifestyles for me (though I suppose I could do jumping jacks at rest areas?). It’s always so fascinating to me how different all diabetics are: I know some of my diabetic friends find activity a wildcard in diabetes management whereas I feel it helps control things.

Barbara: You began drawing black and white cartoons because you had diabetes complication that affected your eyes and you couldn’t see color for a long time, right?

Haidee: Yes. I have severe retinopathy that led to two vitrectomies, both with scleral buckles (a band that repairs a detached retina). This was in my early 20s, so close to 30 years ago/early 1990s, when both procedures involved a six-hour surgery and incredibly slow recoveries. I was in the hospital for days and had to keep a face-down position for two weeks to keep a gas bubble pressing the retina in place. I was using a cane for about a year and started the process of learning Braille (neuropathy soon put an end to that!). Needless to say, one surgery was more successful than the other and I have very low vision in my left eye. I have color loss, for sure, but as an artist, I’ve made it work and it’s certainly nowhere near my biggest complaint! I see double, I have flashes and floaters, facial blindness, no depth perception, I see things that aren’t there and miss objects right in front of me. It’s the most frustrating part of this disease for me and affects everything I do. I guess by this point in life I’ve accepted it, but I still don’t like it—my life has definitely been limited as a result.

Barbara: How old were you when you were diagnosed?

Haidee: Two and a half. From what I’ve been told I was misdiagnosed for about a year. The grand mal seizures—caused by low blood sugars—led to a diagnosis of epilepsy and, I guess, my parents did quite a bit of running around. Eventually I ended up at Joslin where I spent most of my childhood—not literally, of course, but frequently enough to make it feel that way. Joslin used to be the singular hub of the diabetes universe, so we were all lucky to have it so close. I was part of that place’s history when it was a stand-alone institutional beacon! Now diabetes (type one and two) has exploded to the level that most hospitals need to provide diabetes specialty care of their own. The old, historic building in Boston is being repurposed for cancer research, I believe. It’s emotional for me, like selling the family farm.

Maybe if we start a rumor that the ghost of Elliot Proctor Joslin roams those halls with a glass syringe, we’ll eventually get the place back?

Barbara: So, you started out with your black and white line drawings, but now your artwork is vibrant with color.

Haidee: Right. They were all black and white line drawings because that’s what I could see at first. I also kept a journal right after my surgery—I was an avid journal keeper until about the age of 40—using a big, fat pen that crawled up the pages because I had no sense of a horizon line. Neither one made too much difference, of course, because the retinas were healing. The writing looks like a kindergartner did it.

Like I said earlier, I’m still colorblind now, but not in the way that you typically hear. I can tell what colors work together and what families and tones work together. Ultimately that’s why I use bold colors in larger paintings: vibrance is easier for me to see than subtle color changes. My house is full of strong colors, too. Nothing really “goes together,” but it all works as a whole. The dragonfly and insect illustrations are a whole different ballgame, and I have ways of matching and contrasting colors, which includes asking other artists in my studio building to tell me which tube is deep magenta and which is vermilion!

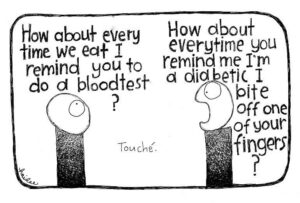

Barbara: What emotion do you think your black and white cartoons are expressing?

Haidee: I’m pretty sure the general themes that inspire my diabetes cartoons are as follows: impatience, feelings of being misunderstood, empowerment, general criticism of the healthcare industry, and the obvious frustration with the entire world—not in that order, mind you. Ultimately, I’m speaking to the diabetes community with the intent of saying, “I see you.” I often use the word commiserate because of the dual meaning: I hope people will empathize/sympathize with the situations and feelings that inspire the images but also feel strengthened and uplifted by them. A double punch. At the end of the day, they come from a place of humor but are inspired by circumstances and feelings that often aren’t.

Barbara: Are you working on another book of cartoons?

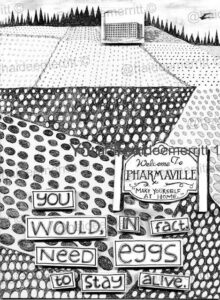

Haidee: Not actively. That said, I have a whole book that’s already illustrated. I need to rewrite the text. (Big sigh.) In a nutshell, it’s about insulin not being a cure for diabetes; however, from there I made a needlessly confusing allegorical story where eggs symbolize insulin—doesn’t exactly sound like a bestseller unless there’s a sentence or illustration when the whole narrative snaps together for an a-ha moment. That moment hasn’t yet arrived. But the illustrations are amazing, some of my best ever. Something will eventually come of it.

I have a few characters I’ve developed—such as Bad Pancreas—which I’d enjoy expanding. And, of course, I have boxes and boxes of other cartoons. (The fact that I actually pen each image with ink on illustration board is a story for another interview.) What it all comes down to is finding a way to make money to support the thing I love to do. Artists are notoriously bad at marketing, a conversation I literally have every other day with fellow artists; it’s obviously something I need to focus on.

Barbara: Some type ones live on very restricted diets. But you enjoy food.

Haidee: Oh yes, I love food. It’s one place in my life I find joy. The primary reason I work out is because food is important to me and I want to alleviate guilt. Calories in, calories out. I’m food motivated, just like my dog! For me, it’s a social thing, too—a way to connect with friends. I live in a small coastal town that’s a regional mecca for restaurants so there’s always somewhere new to try or an old favorite to revisit.

Barbara: Tell me what most concerns you as you’re getting older with T1D?

Haidee: I know I may have to handle things alone; that’s the worst. I’m not quite sure what my needs are going to be, but it’s already been like that every day: as an artist, I’m used to not knowing what’s coming down the pike, whether in the form of work or income. Between diabetes and my career choice, every day is full of uncertainty.

Since I don’t know life without diabetes it’s hard to separate my “self” from the condition. I mean, I don’t like wrinkles and thinning hair, but I sure don’t like losing feeling in my hands and feet either—it’s all just part of the same aging body. I’m not ashamed to claim I’m a type one: I definitely feel like I’m defined by it. I’d rather tell others up front than have to explain some of my goofier actions to them.

You know, when I meet another diabetic my age or above, I compare it to seeing two old-timers meeting on the street: they may never have set eyes on each other before but automatically they reach for each other’s hand and refer to them as “sweetheart” or “my dear.” Or, same vein, like a soldier who served during war meeting another veteran. They seem cut to through details and move right to the heart of things. We see each other’s scars. We acknowledge each other’s battles and achievements. To endure the struggles and get to this place in life is a success in itself.

Barbara: You have worked in the diabetes community and industry in the past.

Haidee: Years ago, I worked at Insulet Corporation. I was a blogger for them, and I did a monthly cartoon. I worked for Diabetes Mine. And for Insulin Nation. I Illustrated Riva Greenberg’s amazing book Diabetes Do’s & How-To’s. I contributed to so many websites, lectures, providers, fundraisers—I see my cartoons and illustrations being used all the time.

When I started promoting my work at ADA, AADE, and DTC I had a lot of passion for getting my work in circulation. It was a fairly novel approach at the time, less sterile and more grassroots, with lots of gorilla marketing.

Barbara: Do you make your fulltime living as an artist now?

Haidee: Sadly, no. I initially got my BA in English and Classics; I went back to school for Horticulture and had a residential gardening business for 22 years (creating art all the while). I retired from that a few years ago and now do Airbnb and art fulltime. Really, I do everything that any other artist does: I just try to cobble it together. You could say I’ve had many careers, but art has always been the one constant. I feel as though my work is therapeutic for me and, hopefully, for others. Yes, always a major outlet for me: some people do yoga, I do art!

You can see Haidee’s artwork for sale on her website

Her books, One Lump or Two, FingerPricks, and The Sweet Taste of Misery, are available on Amazon.

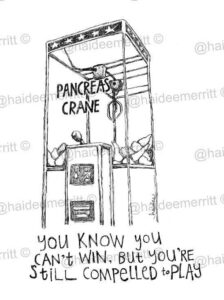

And here are a couple of her favorite cartoons:

And a sample of her dragonfly art:

And finally, from her new cartoons, where eggs are being used as a metaphor for insulin:

Have you read all the way to the end of this article? If so, CLICK HERE to complete a form to enter your name into drawing to receive a free copy of one of Haidee’s books.

(This form will close two weeks after the publication date of this article.)

Barbara Giammona is a T1D diagnosed later in life. She worked in technical and corporate communication for nearly four decades. She is part of the founding team of T1Dto100. In retirement, she splits her time between homes in Southern California and the New Jersey Shore.

Recent Stories & News

When the Doctor Needs a Checkup

A summary of a New York Times article depicting the struggle of doctors as they age out of their careers and best practices for addressing the issue.

TCOYD Podcast Ep 92: Inflammation and Diabetes with Dr. Jennie Luna

Taking Control of Your Diabetes (TCOYD) hosts Dr. Steve Edelman and Dr. Jeremy Pettus sit down with endocrinologist Dr. Jennie Luna to discuss inflammation and diabetes.

How to Spot the Subtle Thinking Patterns That Can Accelerate Dementia

A recent study suggests that constant, repetitive patterns of negative thinking, a ‘fatalistic attitude’, could lead to earlier onset or amplified symptoms of dementia. In short, constant negative thinking could cause or amplify dementia.

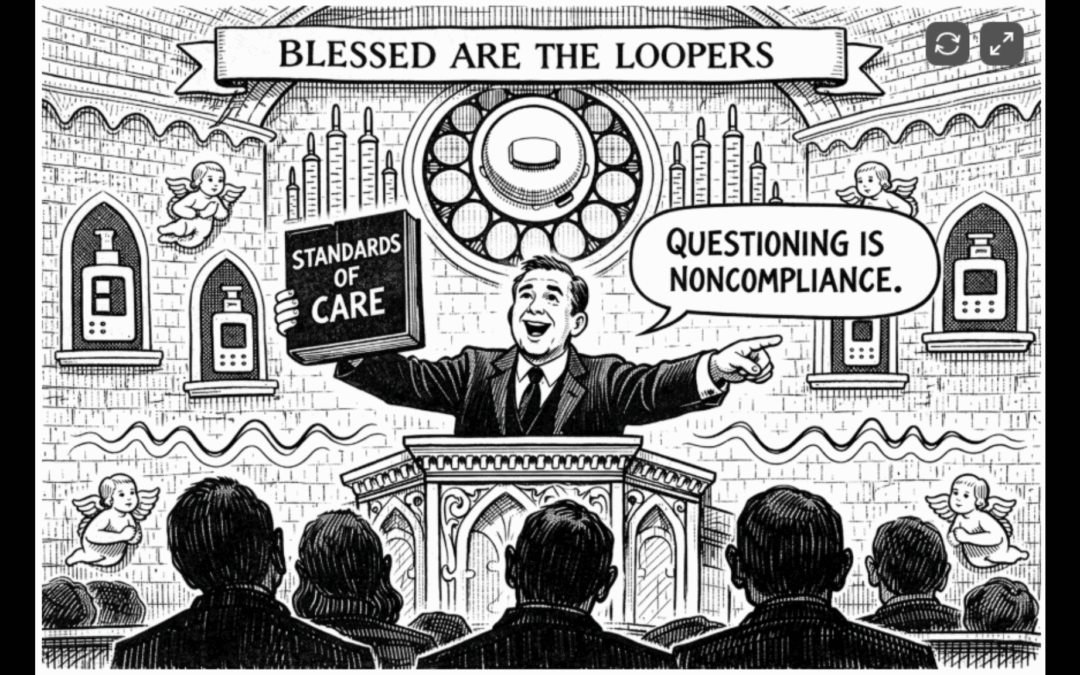

Standards of Care: Who Defines it, How, and Why it Matters

The American Diabetes Association’s “Standard of Care” audience is not your average consumer. It’s clinicians. The intention is that clinicians treat ratings as a starting point, then consider exceptions and carve-outs to determine whether the intervention is appropriate for a given patient. With very few exceptions, the term “standard of care” is rarely ever a simple statement of support with no carve-outs.

LGBTQ+ Webinar

For more information about issues facing LGBTQ+ older adults, please check out the Justice in Aging upcoming webinar with SAGE and Lambda Legal.

0 Comments